On Being "the Only One" at Work

Integration after the civil rights movement of the 1960s has been figured as a victory, but it comes at a cost.

Have you ever been the only one? Are you currently the only one?

In the midst of the civil rights struggle and on the eve of his assassination, movement leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. expressed concerns about the objectives of desegregation. His friend and fellow freedom fighter, the actor Harry Belafonte, stated that Dr. King told him “We have fought hard and long for integration, as I believe we should have, and I know we will win, but I have come to believe that we are integrating into a burning house.” King’s worry was not about Black folks’ ability to get along and get by, but his fear “that America has lost the moral vision she may have had, and … that [she] does not understand that this nation needs to be deeply concerned with the plight of the poor and disenfranchised.”

The torch of King’s Poor People’s Campaign has been revived by the Rev. Dr. William Barber which continues the fight for the soul of America, just as earlier freedom fighters such as Frederick Douglass—the self-emancipated formerly enslaved abolitionist leader, newspaper publisher, and author—and W.E.B. DuBois—the Harvard-educated liberationist, author, philosopher, and founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People—had in prior eras. Black people have been envisioned as integral to this process (as the title of DuBois’s book The Souls of Black Folk [1903] suggests), but we have yet to be fully welcome.

Although, in principle, integration (and its recent rebranding as “inclusivity”) is often celebrated as a clear victory, in reality, it came with devastating consequences. As Dr. Noliwe Rooks, W.E.B. DuBois professor of Africana studies at Brown University, has observed, integration meant the firing of Black teachers as Black students matriculated to formerly all-white schools. And those Black children who we now celebrate as pioneers of the integration movement were frequently physically abused and psychologically terrorized by the white students, faculty, and staff at their new schools. One of the students known as the “Little Rock Nine” who integrated Little Rock Central High School, Carlotta LaNier (formerly Walls), “endured daily indignities, threats and violence. Students spat on her and yelled insults like ‘baboon.’ They knocked books out of her hands and kicked her when she bent down to pick them up.” Her fellow integrationist, the late Jefferson Thomas, was knocked unconscious at school. It is important to remember that LaNier and Thomas were only 15 years old at the time.

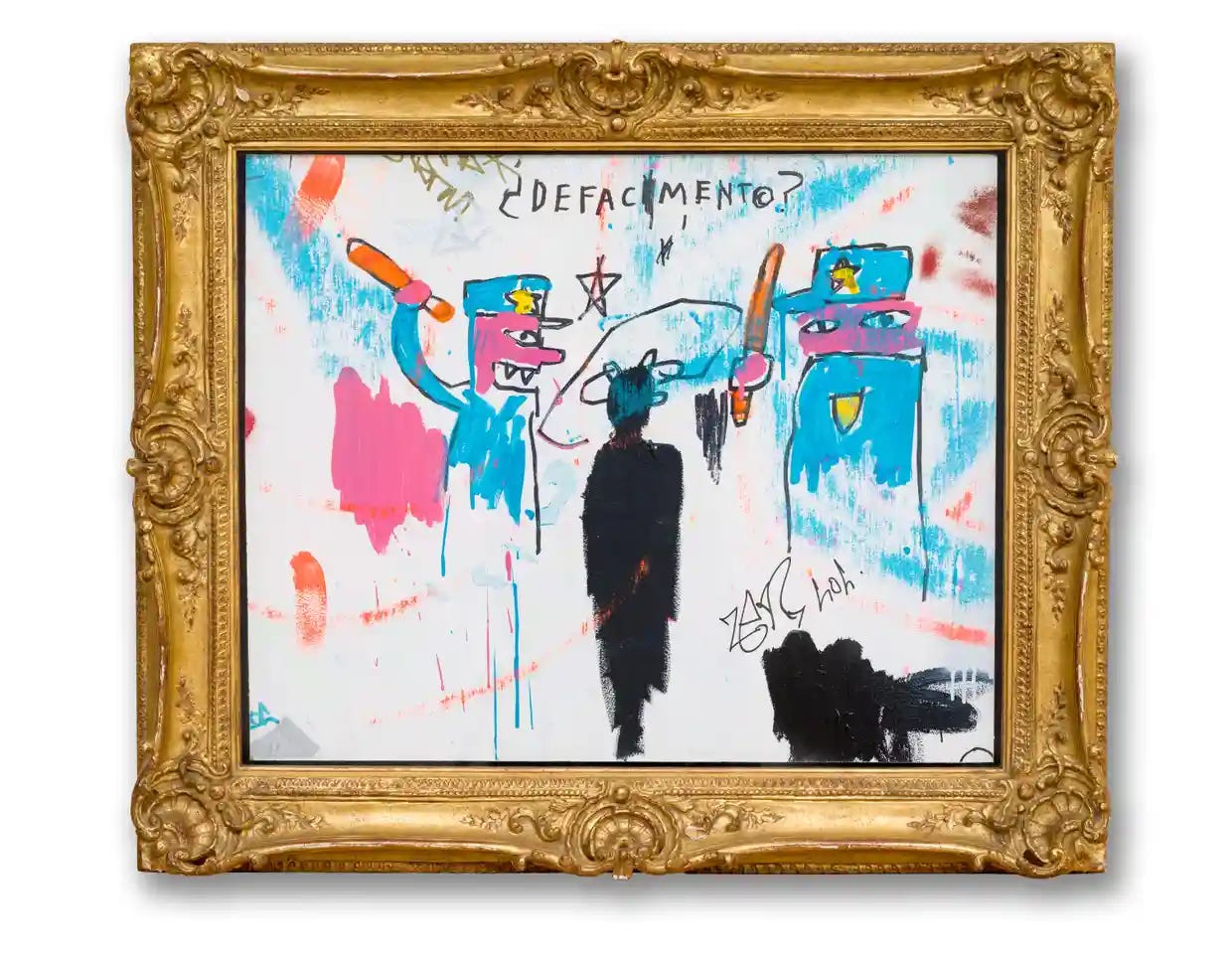

Curator and University of Delaware art history Ph.D. candidate LaTanya Autry recently wrote about the obstacles that were set before her as she attempted to assert her compassionate scholarship on Black resistance to antiblack violence at her workplace. Autry’s article comes not two years after another Black curator named Chaédria LaBouvier exposed the theft of her labor and scholarship at another arts institution whilst developing an exhibition on the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and his painting “Defacement”—the famous painter’s response to the 1983 killing of 25 year old African American graffiti artist Michael Stewart by New York Transit police. These two Black women testify to the experience of having one’s competency in and sensitivity toward blackness interrogated, degraded, and dismissed within a majority white workplace.

Autry and LaBouvier’s stories of workplace abuse while addressing the fact of antiblack racism and violence are not rare. They are vivid reminders (for those who need it) that violence is directed at Black people and, in these scenarios, at Black women in particular when we are simply doing our fact-based work. I, too, know this experience of violence which, though not immediately lethal, may well contribute to the slow death of ourselves and others as we attempt to make a way out of no way in a house that is on fire. After a meeting during which I received an astonishing and disproportionate amount of vitriol, I checked the health data from my watch, wondering if the heart racing I felt in my body registered on my device.

I know, as a Black woman who has been one of or close to the only on campuses throughout my life, that our testimonies are often ignored and that what we claim as evidence is rejected. It may not convince anyone else, but I was perversely reassured to see that, despite not moving from my position during the meeting, my heart had spiked from its average resting rate of 73 bpm to 135 bpm.

I do not have a solution, but at least I know my reality. I also know what my real job is: to take care of myself and, where I can, to take care of my similarly embattled peers. Though we may appear to our colleagues at work to be the only ones, we are definitely not alone.